Source: The Telegraph. Text by By Nataliya Vasilyeva, RUSSIA CORRESPONDENT and Emma Gatten, ENVIRONMENT EDITOR

Source: The Telegraph. Text by By Nataliya Vasilyeva, RUSSIA CORRESPONDENT and Emma Gatten, ENVIRONMENT EDITOR

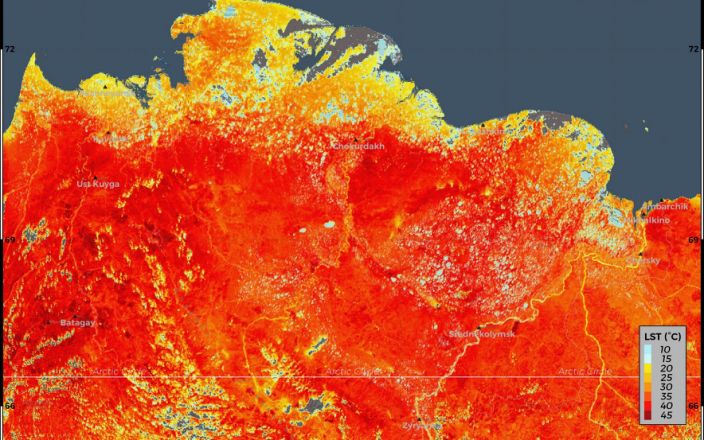

Photo: The Telegraph: "A record-breaking temperature of 38C was registered in the Arctic town of Verkhoyansk on Saturday, June 20"

The northernmost town in the Arctic, Verkhoyansk is one of the coldest inhabited places on Earth and regularly records some of the world’s lowest temperatures.

However, this week it made headlines when it reached a sweltering 38C, the highest temperature since records began 150 years ago.

Locals are used to swinging between extreme temperatures, with summers regularly reaching 30C, but this was something different, said Ayta Baisheva, who works on one of the region’s many reindeer farms, about 250 kilometers south of Verkhoyansk.

“We have seen a freaky heatwave. It’s really hard for us to bear this heat,” said Ms Baisheva who recently returned from the north of Yakutia, close to Verkhoyansk, where her husband and son are now tending to reindeer.

“The reindeer herders were the first to notice that something was wrong: reindeer started to feel unwell. They suffer from dehydration and don’t want to eat. Deer fawns are getting weaker.”

But none of this has come as a surprise to climate scientists.

“Temperatures in both May and averaged over the last six months are the highest in our records for western Siberia,” said Zachary Labe, a researcher in atmospheric sciences at Colorado State University.

Warming temperatures have contributed to the second lowest Arctic sea ice on record, and to wildfires raging across Siberia.

“Decades of climate model projections have shown that the Arctic is expected to warm more than twice as fast as the rest of the globe,” Mr Labe said, because of feedbacks in the climate system which mean that, for instance, as warming temperatures melt snow cover, the ground can no longer reflect the sun’s rays. “We are now seeing the impacts of these extremes in real-time.”

Talk to the locals in Verkhoyansk and you will be unlikely to hear about climate change, or get a sense of wider crisis.

Russian President Vladimir Putin is yet to speak about the heatwave, and climate change barely reaches the Kremlin’s agenda.

Several districts of Yakutia have declared a state of emergency, but firefighters in the region only have the resources to put out a fraction of the wildfires, and are simply leaving blazes in remote, hard-to-reach areas to burn out.

Extraordinarily persistent 'warmth' over parts of Siberia during the boreal spring - exceeding more than 7°C above the 1951-1980 climate baseline!

[Data from @NASAGISS GISTEMPv4] pic.twitter.com/c4rGTp3851

— Zack Labe (@ZLabe) June 23, 2020

But warming in Siberia has implications for us all, says Dr Christina Schädel, the lead coordinator of the Permafrost Carbon Network. “What happens in the Arctic does not stay in the Arctic,” she said.

Vast swathes of the Arctic is made up of permafrost - ground that has been frozen for at least two years but up to tens of thousands.

That permafrost contains huge reserves of stored carbon from the organic matter it contains; twice as much as is currently in the atmosphere. As the permafrost melts, that carbon is released and adds to the global greenhouse effect.

Rising Arctic temperatures have already led to the thawing of permafrost in several locations, but scientists warn there could be a looming ‘tipping point’ of temperatures which would see a rapid melting.

“That permafrost once thawed is never going to freeze back in our lifetime,” said Dr Schädel. After a certain point, “the process is unstoppable and it’s irreversible.”

A Russian mining firm blamed sudden permafrost melt for a historic oil spill in early June that left more than 20,000 tons of diesel fuel in two rivers near the Arctic city of Norilsk.

Environmental groups said the spillage should have been foreseen, but the event underscored the vulnerability of Arctic infrastructure.

Wildfires are also adding to the carbon in the atmosphere, contributing more carbon in the past 18 months than the total from the previous 16 years.

We don’t yet know the scale of the carbon trapped in the permafrost and what the ultimate impact could be on the atmosphere. “There are gaps in our knowledge,” said Dr Schädel.

Scientists say the only way to halt the potential catastrophe developing in the Arctic is to slow climate change.

“I am still optimistic that we can do it but we just don't have that much time left,” said Dr Schädel.