History

Reindeer and people have a connection that is thousands of years old in what is today called Norway. First by hunting, then through domestication and herding. Archaeological sources such as hunting pits, stone carvings and settlement excavations speak to this connection. In 98 AD, the Roman historian Tacitus wrote about a strange people in Thule, who used fur clothes, hunted reindeer and travelled with skis.

In the 800s the Norwegian chief Ottar visited King Alfred and the English court and Ottar related to the king about the Sámi and that reindeer were domesticated and managed in herds. This is the first written source of domesticated reindeer herding and is often referred to. However archaeological research is consistently pushing the date of domestication of reindeer and the development of reindeer herding further back in time. Writings after that time tell that the Sami are using domesticated reindeer for transport and milking.

In the 16th 17th and 18th centuries, Sweden had imperial ambitions and this increased the tax burden on Sámi reindeer herding, which would appear to have stimulated a shift in reindeer herding practices. Sámi reindeer herders where nomadic and moved with their reindeer herds between winter and summer pastures. In the mountain areas an intensive reindeer herding took shape – where reindeer where monitored daily.

The Sámi people lived and worked in so-called “siiddat” (reindeer herding groups) and reindeer where used for transport, milk and meat production. The Siida is an ancient Sámi community system within a designated area but it can also be defined as a working partnership where the members had individual rights to resources but helped each other with the management of the herds, or when hunting and fishing. The Siida could consist of several families and their herds.

Borders

Sámi reindeer herding in present Sweden, Norway and Finland has historically been and is in many ways still affected by the creation of national borders. Borders became barriers to reindeer herding which had, since time immemorial been a livelihoos that migrated between different areas. The first boundary which affected the Sámi reindeer herding was drawn between Norway/Denmark and Sweden/Finland in 1751. To this border agreement was made a substantial allowance of 30 paragraphs on the rights of the nomadic Sámi – later often called the Lapp Codicil (Lappekodicillen) or the Magna Charta of the Sámi.

The aim with the Codicil was to secure the future reindeer herding for the Sámi people affected by the border. The states agreed that regardless of state borders, the reindeer herding Sámi should be able to continue to migrate with their reindeer to the other kingdom in the same way as they had done before the border demarcation. The migrations have since 1919 been regulated between Norway and Sweden in different so called reindeer grazing conventions (renbeteskonventioner) which are based on the Codicil. The last convention was negotiated 1972 and was in force until 2005. Sweden and Norway are negotiating on a new convention.

During the 1900’s meat production becomes increasingly important and reindeer herding becomes more extensive. In the 1960’s, the Sámi reindeer herders started to introduce new technologies – the so called snow mobile revolution in their work with reindeer. Later came other mechanical aids, such as ATV’s, motorbikes and helicopters. Today such tools are major feature of modern reindeer herding. This has had a variety of impacts on reindeer husbandry and as herders no longer ski or walk with reindeer, the relationship has changed somewhat. Today’s reindeer herding requires large areas, reindeer are often frightened and are forced to flee from natural pastures. Today’s reindeer are not watched year-round and reindeer wander freely during certain periods.

However, reindeer husbandry would not be possible without the maintenance of traditional knowledge which dates back millennia and is transferred from generation to generation. Its significance remains for reindeer herders because it contains important knowledge about how for instance land should be used during times of extreme weather fluctuation, for example.

Reindeer husbandry today in Sweden is a small industry on a national scale, but both in a Sámi and local context, it has great importance. Reindeer husbandry is not only important economically and in employment terms, it is also one of the most important parts of the Sámi culture. According to the reindeer husbandry act the Reindeer Husbandry should be economically, ecologically and culturally sustainable. In other words, reindeer husbandry in Sweden should be conducted in a way so it gives a reasonable number of entrepreneurs a good living.

Rights to own Reindeer

Contemporary reindeer husbandry in Sweden, is regulated by the Swedish reindeer husbandry act, Rennäringslagen 1971: 437. According to this Act, the right to pursue reindeer herding only belongs to the Sami people. Only a person who is member of Sámi reindeer herding village (Sameby) has reindeer herding rights, in other words, may engage in reindeer husbandry in the Sámi reindeer herding village to which she/he belongs. The reindeer herding right, which is eternal, includes for example the rights of members to also hunt and fish within their Sámi reindeer herding village’s area. These are immemorial rights, which mean that the Sámi have, over a long period used the land without anyone impeding them. Both reindeer herding and reindeer husbandry are terms often used in Sweden, where reindeer herding is the work with reindeer and reindeer husbandry encompasses reindeer herding, hunting and fishing because they all are important industries of reindeer husbandry. (Rennäringslagen 1971:437)

Contemporary reindeer husbandry in Sweden, is regulated by the Swedish reindeer husbandry act, Rennäringslagen 1971: 437. According to this Act, the right to pursue reindeer herding only belongs to the Sami people. Only a person who is member of Sámi reindeer herding village (Sameby) has reindeer herding rights, in other words, may engage in reindeer husbandry in the Sámi reindeer herding village to which she/he belongs. The reindeer herding right, which is eternal, includes for example the rights of members to also hunt and fish within their Sámi reindeer herding village’s area. These are immemorial rights, which mean that the Sámi have, over a long period used the land without anyone impeding them. Both reindeer herding and reindeer husbandry are terms often used in Sweden, where reindeer herding is the work with reindeer and reindeer husbandry encompasses reindeer herding, hunting and fishing because they all are important industries of reindeer husbandry. (Rennäringslagen 1971:437)

A reindeer has to be marked in the ears. A reindeer earmark is a combination of one to many cuts in a reindeer’s ears which all together tells who the reindeer owner is. There are around 20 different approved cuts and in addition some 30 different combinations of cuts, and all those cuts and combinations have their own name. All reindeer in the Sámi reindeer husbandry area shall be marked with the owner’s registered earmark by 31 October the same year as it is born. Before an earmark is implemented, it shall be approved by the earmark committee consisting of 3-5 members. After approval the earmark shall be announced. The way to describe a reindeer earmark on may vary from area to area because of dialect diierences. Here is one way to describe the earmark on the image in Sámi: Gurut bealljis guobir. Ovddal biehki nala sárggáldat. Ma?il guokte biehki, bihkiid gaskkas sárggaldat. Olgeš belljis liekci. Ovddal vanja vuolde sárggaldat. Ma?il biehki vuolde sárggaldat.

Sámi villages and members (Sameby)

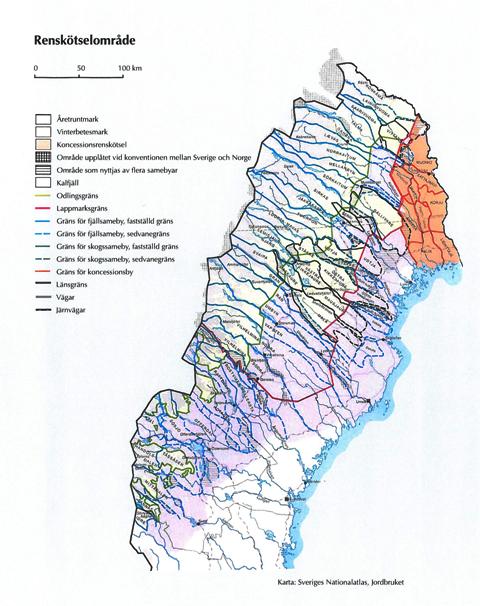

Sámi reindeer herding in Sweden is divided into 51 Sámi reindeer herding villages which are both economic associations and geographical areas. Of those are 33 mountain and 10 forest Sámi reindeer herding villages, in this text also called Sámi villages, and 8 concession Sámi reindeer herding villages, here referred to as the ‘concession villages’. The difference between a mountain Sámi reindeer herding village and a forest Sámi reindeer herding village is that reindeer herding in the forest villages is more static and is conducted in forested areas while mountain reindeer herding is characterised by long migratory routes between summer and winter pastures. Concession villages reindeer herding is very different from the first two, as they engage in reindeer husbandry with special permission from the County Administrative Board (Länsstyrelsen).

Concession villages exist only in the Torne Valley (the area on the Swedish on the river between Sweden and Finland). The County Administrative Board determines the boundaries of the concession villages. The reindeer in the concession villages are owned by non Sámi who also often own the land on which their reindeer graze. However, according to the reindeer husbandry Act the actual reindeer herding in a concession village must be conducted by a Sámi. A reindeer owner in a concession village is not allowed to own more than 30 reindeer.

A Sámi reindeer herding village has a board voted in by a majority in the village during their annual meetings. The Board has the mandate to conduct the village’s work. Sámi reindeer herding village rights and duties are statutoried; inter alia, in the reindeer husbandry act. According to the Act, the Sámi village is responsible for ensuring that reindeer herding is conducted most effective way economically and shall organise reindeer herding in the village’s reindeer herding area in the best way for the members’ common interest. Membership numbers in the Sámi villages vary greatly and it is the Sámi village’s annual meeting, which decides who may join the village. Annual Meeting decisions concerning membership can be appealed to the Sámi Parliament.

A Sámi village has both reindeer herding members and ordinary members. A reindeer herding member is according to the Act, understood as a member who by him/her self or someone in his family conducts reindeer husbandry with their own reindeer within the villages grazing area. A reindeer herding member has the right to vote in certain matters that an ordinary member does not have. An ordinary member is a Sámi who takes part in reindeer herding within the villages area, a Sámi who has been involved within the villages reindeer herding and has not left reindeer herding for other work or a wife/husband or a child who lives at home to a person listed above. In Sweden it is possible to own reindeer without being member of a Sámi reindeer herding village. In that case the person needs a registred reindeer earmark and a permission to be a reindeer owner (skötesrenar in Swedish and geahccobohccut in Sámi) within a village.

Reindeer herding employs about 2500 people in Sweden and the number of reindeer owners is a total of about 4 600 people. According to figures from 2005, 77 % of the country’s reindeer are owned by men.

- (Rennäringslagen 1971:437)

- (www.sametinget.se)

Reindeer Herding Areas

According to the reindeer husbandry Act reindeer herding may be conducted on both private and state lands where reindeer herding is permitted as according to the law. This means that private land owners’ lands also may be used for reindeer grazing. Lands used for reindeer herding are divided into year-round-lands and winter pastures. In the year-round-lands reindeer herding, as the name relates, may be conducted year-round and in winter pastures only between October 1st and April 30th. The Act is clear as to where the line between these lands and pastures lies and defines it accordingly.

The reindeer herding area covers nearly 40 percent of Sweden’s surface. The northern border is within Könkämää Sameby in the Norrbotten County and the southern border is in Idre Sameby in Dalarna County. Some Sámi villages in Sweden have during a very long time had summer pastures in Norway. These transboundary rights are based on the so-called “Lappekodisillen” which constitutes an addition to the border agreement between Denmark/Norway and Sweden from the year 1751. The states agreed that regardless of state borders, the reindeer herding Sámi should be able to continue to migrate with their reindeer to the other kingdom in the same way as they had done until the border demarcation. These migrations over the border have since 1751 been regulated in different so called reindeer grazing conventions (renbeteskonventioner) between Norway and Sweden. The last convention was negotiated 1972 and was in force until 2005. Sweden and Norway are negotiating on a new convention.

(Rennäringslagen 1971:437)

Management of Reindeer Husbandry

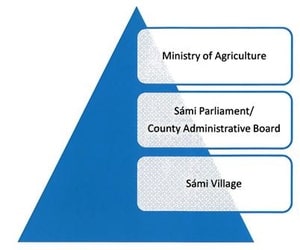

The management of reindeer husbandry is divided into 3 main levels; the national, the regional and the local level.

On the national level reindeer husbandry issues are administered by the Ministry of Agriculture and the Minister of Agriculture is the responsible minister for reindeer husbandry issues. The state has the responsibility for how reindeer herding can be conducted. The Swedish Sami Parliament is the central administrative authority in reindeer husbandry issues and the government’s expert authority. The parliament shall for example develop and adopt certain rules for reindeer husbandry as well as handling funding for the promotion of reindeer husbandry.

On the national level reindeer husbandry issues are administered by the Ministry of Agriculture and the Minister of Agriculture is the responsible minister for reindeer husbandry issues. The state has the responsibility for how reindeer herding can be conducted. The Swedish Sami Parliament is the central administrative authority in reindeer husbandry issues and the government’s expert authority. The parliament shall for example develop and adopt certain rules for reindeer husbandry as well as handling funding for the promotion of reindeer husbandry.

On the regional level the County Administrative Board (Länsstyrelsen) primarily handles issues that widely affect reindeer husbandry. The Board has for example the responsibility to manage state lands north of the so called ‘cultivation border’* (odlingsgränsen) – lands where many Sami villages have their year round lands, such as important building permits and hunting and fishing applications. The Board will also decide on the maximum number of reindeer for the Sami villages. Year 2007 where some issues concerning reindeer husbandry moved from the Board to the Sámi Parliament.

On the local level the Sámi village’s internal affairs, is managed within the framework of the reindeer husbandry Act, dealing with issues such as the Sámi village’s economy and the Sámi reindeer herding village’s joint work. A Sámi village can have several summer and winter siidat who do the practical work with the reindeer during the periods when the herd is divided.

The cultivation border is an administrative border which was drawn in 1867 by the state. It separates the mountain regions from the rest of the country. At the time when northern parts of Sweden where colonized by settlers, buildings where not allowed above the cultivation border. In the area above the border the Sami should be able to have their reindeer all year without disruption.

- (www.sametinget.se)

- (www.bd.lst.se)

- (www.fjallen.nu)

Number of Reindeer

The number of reindeer in Sweden fluctuates and during the 1900’s it has varied between 150000 and 300000 reindeer. In Sweden the reindeer numbers where 253 000 year 1995, 221 000 year 2000 and 220 000 year 2007. The number of reindeer is counted after slaughtered reindeer are withdrawn from the herd, and before the calving starts, which is usually in may. For each Sámi village, the maximum number of reindeer is decided by the County Administrative Board and the reindeer are counted each year by the reindeer herders themselves. On the individual level there are no maximum numbers for reindeer.

- (Rennäringslagen 1971:437)

- (www.sametinget.se)

- (www.bd.lst.se)

Economy

The economic situation among reindeer herders in Sweden varies greatly, and today’s reindeer herders have to adapt to a wide variety of changes in the local, regional and national economy. Reindeer and their pastures should be managed on both a rational and sustainable manner, while at the same time reindeer herders need revenue to survive. Reindeer herding is in terms of taxation seen as a for-profit-business and for a reindeer herder the most commonly filled tax form selected is as a private entrepreneur (enskild firma). The basic rule for this is that all income should be taxed, with the exception of the income that is tax free, and business costs that are tax-deductible. In Sweden there are around 900 reindeer husbandry companies. One company can include one or more reindeer owners and family members and in a Sami village are some or many reindeer husbandry companies.

Today, the income of individual reindeer herders consists of the production of meat and raw materials such as skins, bones and horns. Additional sources of income include financial subsidies and compensation. The income of the individual may consist of additional processing, sale of services, additional industries and paid work.

Research by the Sámi Instituhtta in 2006, show that reindeer herders incomes varies depending on which region they herd reindeer. In general reindeer herders in the southern parts of the Swedish reindeer herding area gain more income from meat production than compensations and subsidies while it in general is the opposite for reindeer herders in the northern parts. The number of reindeer and the production of meat are usually related. It is not unusual that when the total number of reindeers decreases, the total value of meat production also shows a falling trend. In general, the differences in the income picture between reindeer herders in the north and south is likely because the reindeer numbers in the north are lower per reindeer owner and the owners are many, while the reindeer numbers per owner in the south parts are higher. Most reindeer herding families also have incomes from salaried work.

- (www.sametinget.se)

- (Diedut, Analyse av den samiske reindriftens økonomiske tilpasning, Sámi Instituhtta, 2006)

State economic support for reindeer husbandry

State economic support for reindeer husbandry in Sweden consists primarily of price support for reindeer meat. Price support is calculated according to weight and paid to each reindeer owner per slaughtered reindeer at a control slaughterhouse. In 2007 the price support was 8.50 SEK (0,8 € ) per kilo for meat from mature animals and 14 SEK (1,32 €) per kilo for calves. In addition, 0,5 SEK (0,047 €) per kilo is paid in the form of marketing support. In 2006/2007, 74 775 reindeer were slaughtered in control slaughterhouses and the figure for 2003/2004 was 48 275 reindeer. The increase in the number of slaughtered reindeer is mainly due to marketing efforts.

Annually, the government decides the amount of funding for the promotion of reindeer husbandry and this sum varies from year to year. For 2009 a total of 55 718 000 SEK (5.2 M €) has been proposed for the development of reindeer husbandry. From this sum, funds are allocated to price subsidies, risk reduction measures, the costs of mediation between landowners and the Sámi villages, and the costs associated with the Chernobyl accident among other elements.

In 1996 there was a nuclear accident at Chernobyl wich widely and adversely affected reindeer herding in Sweden, especially reindeer herding in Västerbotten and Jämtland counties. The same year that the accident occurred, about 27 000 reindeer were destroyed, which represented 78% of the number of slaughtered reindeer the preceding year. In 1993/1994 11 669 reindeer were forcibly discarded. Today, only a few percent are discarded and there is no risk anymore from eating reindeer meat because the cesium levels has decreased sharply. During the years 2006/2007 cage was only 38 reindeer. Carcasses which have a caesium level over 1 500 becquerels are discarded. The state replaces reindeer owners for losses caused by the accident.

Years when the winter pastures are locked because of the frequent freeze thaw events, Sámi villages in Sweden can apply for disaster subsidies from the Sámi Parliament for costs associated with providing reindeer with articial feed. Conditions include the need to feed reindeer for at least 60 days and that the state has conducted surveys in the Sámi village’s area. If a Sámi village that has applied for support meets all the conditions, the Sámi Parliament can grant support of up to 50 percent of the feed costs.

Other state assistance that may be relevant for the reindeer husbandry, and which is not included in the promotion allocation, is ‘rural support’ (landsbygdsstød), EU support and environmental compensation.

- (www.sametinget.se)

- (Regeringens regleringsbrev för budgetåret 2008 avseende Sametinget)

Loss of Pastures and Encroachment

Reindeer need large and undisturbed areas during the whole year. For many years, reindeer husbandry in Sweden has had to grapple with intrusions, such as mining, hydro power development, wind power development and industrial scale logging. New activities are continually encroaching on reindeer pastures. Encroachments into reindeer pastures grazing conditions are seen among both reindeer herders and researchers to be one of the largest threats to the future of Sámi reindeer husbandry.

In Sweden, the environmental law 1998:808 is the primary piece of legislation which regulates permits for environmentally hazardous activities. The developer must in connection with their application for a permit nearly always have to implement an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). An EIA is usually done by a consultant to the developer. The EIA is intended to provide a holistic view of the environmental impacts and effects of various planned activities. If a planned activity will affect a Sámi reindeer herding village/-s, the developer must describe the effects on reindeer herding before the deciding authority, which can be the County Administrative Board, can decide on whether to give permission to the developer. In Sweden, Sámi reindeer herding villages sometimes have difficulties to be considered as concerned parties in development cases. This means that they are not heard, nor do they have the opportunity as injured parties to appeal any permit if necessary. In 2007, the ombudsman against ethnic discrimination (Diskrimineringsombudsmannen -DO) sued Krokoms municipality in the county of Jämtland for ethnic discrimination. The municipality failed to hear Jovnevaerie Sámi reindeer herding village in relation to a case concerning building permits which affected the Sámi village reindeer pastures. DO demanded that the Sámi village be compensated for ethnic discrimination. The municipality’s systematic breach of Sámi rights as concerned parties were also, according the DO, a crime in itself, in both Swedish law and international conventions. DO found that the municipality through its actions overrode Sámi property, and were negligent in their protection of the Sámi as indigenous people on the basis of their minority status.

If a planned activity or measure, which does not require a permit, may significantly change the natural environment, the operator shall consult with the concerned authority and for example any concerned Sami reindeer herding village/-s. The Organisation for Sámi in Sweden (Svenska Samernas Riksförbund, SSR) has together with the Sámi reindeer herding villages in Sweden begun to request that operators initiates Social Impact Assessments (SIA – SKB in Swedish). In a SIA the effects of any positive or negative change that occurs (for example in people’s lives, culture, society, political systems and health can be assessed). Sámi reindeer herding villages have repeatedly pointed out that environmental impact assessments do not provide sufficient depth and do not take into account the socio-economic and cultural impact of proposed developments, nor do they take account of the Sámi reindeer herding villages traditional land use patterns and the importance of the Sámi cultural landscape. SSR and the Sámi reindeer herding villages therefore urge developers with the help of SIA’s to analyse the cultural and social effects for concerned Sámi villages of planned activities. Under Swedish law the operator is not required to perform a SIA, but an operator who agrees to undertake a SIA should commission and fund it.

Industrial forestry activities within reindeer herding areas often affect large areas of reindeer pastures, so reindeer herders have a strong interest in how forestry is conducted. According to Forestry Law, a Sámi reindeer herding village shall be given an opportunity for consultation on various types of forest activities. According to the Sámi Parliament and the Forest Board (Skogsstyrelsen) the consultations between reindeer husbandry and forestry companies are held, but with varying degrees of success. The forest companies have mostly poor knowledge of lands in respect of the needs of reindeer. Forest companies have been known to not carry out forest operations in the manner agreed by the parties during consultations. In light of this situation, the Forest Board together with six Sámi reindeer herding villages has established Reindeer husbandry plans. The purpose of the plan is to act as a detailed basis for all necessary information for the consultations between forestry activities and reindeer herders. The Forest Board has the responsibility to support the work of the reindeer husbandry plans and the practical work is done by the current Sámi reindeer herding villages and the Sámi Parliament. A great deal of interest has been expressed from all parties in the progress of these negotiations, with a view to extending these types of consultations to other fields such as mining, wind power development and recreational facilities such as snowmobiling. A further eight villages are establishing plans and another 19 villages have declared an interest in doing so.

In Sweden there are several long and ongoing court cases related to reindeer grazing activities. In all these cases, landowners have sued Sami reindeer herding villages for allowing winter grazing on private lands. Private land owners argue that the land in question has not been used for a sufficiently long period of time and Sami reindeer herding villages are not therefore able to claim the right to reindeer grazing on the lands in question. On the other hand, reindeer herding Sami claim that they have been using such lands for reindeer grazing periods long enough for them to receive reindeer grazing rights. In 1998, over 120 landowners sued three villages in the Västerbotten County in the district court arguing that the Sámi reindeer herding villages did not have the right to let their reindeer graze landowners’ lands. The Sami reindeer herding villages won in the district court and the landowners appealed to the Court of Appeal, where Sámi also prevailed. Land owners appealed further to the Supreme Court of Sweden in April 2007, and a decision is pending.

The challenge in some areas is that, to prove the Sámi use of land in court, since the Swedish legal system is based on farming culture, is difficult. It is much easier to prove that some land has been cultivated over 90 years than it is to prove hunting, fishing and reindeer herding, as Sámi did not made major impacts on the nature. In Sweden, the burden of proof is on the Sámi, while in Norway is the opposite: landowners must prove that Sámi usage does not exist.

- (www.sapmi.se)

- (www.sametinget.se)

- (Miljöbalken 1998:808)

Predation

Predators are a major cause of losses for reindeer herders and the predators issue is currently one of the main issues that the Swedish Sámi Organisation, SSR, is working with. Figures from Swedish University of Agricultural Science (Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet, SLU) indicate that 40 000-45 000 reindeer are killed by predators annually in Sweden and that it represents about 55 million SEK (5,17 M €) in losses for reindeer herders, without taking into account the breeding value and value added meat lost.

The goal of Sweden’s predator policy is that there should be a certain number of predators in the Sweden and in recent times, the number of predators in the country has generally increased. Sweden’s predator investigation, Predators and their Management SOU 2007:89 published in December 2007, shows that the number of eagles is about 1 800 and that Sweden’s bear population in 2005 ranged between 2 350 and 2 900 bears. In 2007, the number of lynx was between 1 300 and 1 500. The government’s 2008 target for the number of wolverine has, according to estimates, been achieved. According SEPA (Swedish Environmental Protection Agencies), there are at least 200 wolves and 490 wolverines in Sweden.

According to the law, individuals must accept that their private property, such as reindeer, may be food for predators, for which the state pays compensation. This compensation is paid to the Sámi reindeer herding villages. Inventory counts on predators are performed by the County Administrative Board (Länsstyrelsen) with the assistance of the Sámi reindeer herding villages, and this forms the basis for compensation. The Sámi Parliament administers both the regulations and the funding for the predator census. Sámi reindeer herding villages are reimbursed for each den (föryngring) that is found and approved. For example, a found and approved den of wolverine or lynx entitles a Sámi reindeer herding village to a payment of 200 000 SEK (18 800 €). In 2007 the Sami Parliament paid out a total of 43 950 489 SEK (4.15 M €) to the Sami reindeer herding villages for predation compensation.

The aim is that the compensation should be experienced fair and reasonable and provide better conditions for long-term predator care. The compensation should:

- compensate reindeer husbandries losses

- achieve balance between different interests

- increase the understanding and tolerance of reindeer husbandry and predators

- be fair – as far as possible

- be smooth and prompt

The system explained above was introduced in 1996 and before that a system was in force where reindeer owners and the Sámi villages got compensation for each found reindeer killed by a predator. The problem with the old system was that all killed reindeer where not found and that reindeer owners could lose compensations they were entitled to.

SSR and the Sámi Parliament have been associated with the last state predator investigation, Rovdjuren och deras förvaltning SOU 2007:89, concluding that predators are perceived as being one of the greatest threats to reindeer herding and that the Sámi reindeer herding villages want to have a much greater ability to influence predator compensation and practices. SSR and the Sámi Parliament also express the opinion that this investigation did not sufficiently investigate the effects of today’s predator policy on reindeer husbandry. The Sámi reindeer herding villages and SSR have stated that the level of predation must be reduced to 25 % of current levels in Sweden if reindeer husbandry should continue to thrive in the future.

The question of protecting domesticated and semi domesticated animals against predators has been discussed a great deal for many years primarily between animal owners on the one side and the state/predator organisations on the other. Reindeer herders for example have been stating from a legal point of view that they should be given fairer conditions to remove problem predators.

- (www.sapmi.se)

- (www.sametinget.se)

- (www.naturvardsverket.se)

- (Rovdjuren och deras förvaltning SOU 2007:89)

Climate change

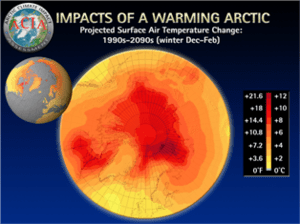

The Arctic Council Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (2005), reflects more than 250 researchers’ assessments of how climate change will affect the Arctic environment and the communities that live there. The report also demonstrates that temperatures in the Arctic are rising faster than elsewhere in the world. These changes will involve, inter alia, shorter and warmer winters, and new varieties of wildlife in the Arctic. Climate Change also may result in increased development in the Arctic, which likely will bring negative affects on the reindeer pastures.

The Arctic Council Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (2005), reflects more than 250 researchers’ assessments of how climate change will affect the Arctic environment and the communities that live there. The report also demonstrates that temperatures in the Arctic are rising faster than elsewhere in the world. These changes will involve, inter alia, shorter and warmer winters, and new varieties of wildlife in the Arctic. Climate Change also may result in increased development in the Arctic, which likely will bring negative affects on the reindeer pastures.

Since reindeer herding is conducted in nature and is very much dependent on the conditions that nature provides, any changes that occur have special impacts on the practice of reindeer husbandry. But no one can yet know with certainty when, how and how much reindeer herding will be affected as a result of increased climate change.

In a government investigation into the impacts of climate change in Sweden from 2007, a reindeer researcher, Öje Danell, predicted that land would be bare for longer and that plant productivity would increase by 20-40 percent. Since snow free time is when reindeer collect important fat and protein reserves, reindeer, according to Danell, can take advantage of this benefit for a longer period of time. However, there remains uncertainty about how the mountain flora will withstand warmer climates couple with the impacts that a warmer climate will have on different insect varieties and how they will affect reindeer. Danell estimates that warmer winters and all that they entail, together with today’s continues encroachments in reindeer pastures, the increasing number of predators, may have such negative affects on reindeer herding in Sweden that within the space of 50 years, it will not be conducted as it is today.